Note: This article was originally found in the March/April 2010 edition of The Home School Court Report magazine, Vol. XXVI No. 2.

* * *

On January 26, 2010, a decision by a United States immigration judge sent a shockwave across the world. In the decision, Judge Lawrence O. Burman granted asylum to Uwe and Hannalore Romeike, who had fled their native Germany in search of freedom from persecution for homeschooling. It was the first case ever to recognize homeschooling as a reason for granting asylum.

Like the courageous English families who fled to Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1620, seeking freedom from religious persecution, scores of German families have been forced to leave their homeland since 2000 in search of freedom to home educate their children. Judge Burman’s unprecedented decision to grant the Romeikes asylum represented a step toward freedom for these families, but infuriated many nonhomeschooling Germans and sparked a national discussion. Joseph Krause, president of the German Teacher’s Association, told Time.com that the decision treats Germany like a “banana republic.”

Mike Donnelly and the Romeike family prepare to testify in the asylum hearing on January 20, 2010

The Romeikes’ asylum victory is the culmination of years of groundwork to protect homeschooling on the international front—but it is only the beginning of the battle.

A Strategy for Freedom

Home School Legal Defense Association has been tracking the plight of German homeschoolers for years. In the early 1990s, then–HSLDA President Michael Farris became aware of the struggles homeschooling families were facing in several European countries during his travels on behalf of Christian Solidarity International. Over the next decade and a half, Farris and the late HSLDA Senior Counsel Christopher J. Klicka visited Germany on several occasions and championed families involved in early homeschooling court cases. HSLDA sought to encourage and connect homeschoolers in Germany and, in 2000, helped to establish one of the country’s first homeschool legal services associations, known as Schulunterich Zu Hause (“Schuzh”). After I (Mike Donnelly) joined HSLDA’s legal team in late 2006, I became the attorney responsible for coordinating HSLDA’s support of German homeschoolers.

As the number of German cases increased through the early 2000s, it became obvious that a comprehensive strategy was needed. Farris (now HSLDA Chairman), current HSLDA President Mike Smith, Klicka, and I were concerned that if Germany could continue to get away with persecuting homeschoolers, other countries might follow its lead. And evidence from some European countries, such as Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland indicate that this concern has merit. In an increasingly small world, such a trend may not stay on the other side of the Atlantic.

We analyzed the legal battle for freedom in Germany and concluded that prospects were not promising. Both of the country’s supreme courts had rejected homeschoolers’ claims. The two courts had said that it was acceptable for German authorities to stamp out parallel societies, implying in their decisions that homeschooling somehow contributes to the creation of parallel societies. The courts also said that homeschooling was an abuse of parental rights. In October 2006, the European Court of Human Rights rejected homeschoolers’ claims and we realized that freedom would not be fully won through the courts in Germany or Europe. In early 2007, Farris and I met with German homeschool leaders and Schuzh attorneys. Together, we laid out a new three-part strategy of legal defense, humanitarian assistance, and political influence.

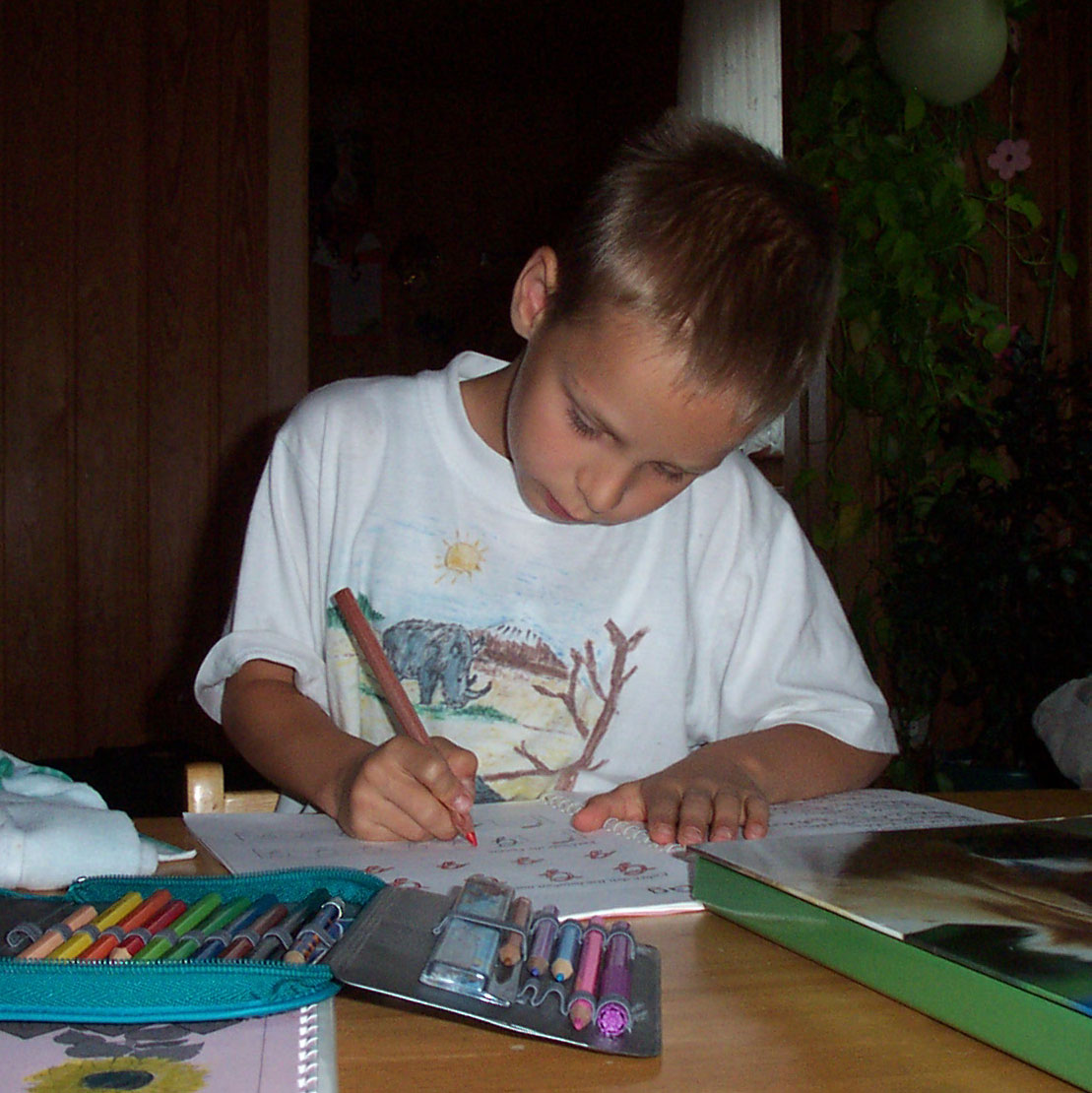

The Romeikes' son Josua intently focuses on his schoolwork in Germany

We knew that laws would have to be changed if there was to be freedom for German homeschoolers. This would require changing public opinion and getting the attention of legislators. Because there were so few homeschoolers in Germany, there was no way they could exert any kind of political influence. And in the face of the German Supreme Court decisions, we knew that officials would need heavy prompting to confront this issue.

In further developing the new strategy, Jim Mason, HSLDA Director of Litigation, suggested considering a political asylum case. He contacted former HSLDA Legal Assistant Will Humble, who was now actively practicing immigration law and who agreed to assist with the Romeike’s political asylum claim. Humble outlined the arguments that would have to be made for such a case, and HSLDA began to look for the right test case.

The first opportunity came in the form of a case that had started back in 2006 when a German family sought protection from the Jugendamt (German social services), which was seeking to remove the family’s twin sons, who were too ill to be taught in a regular school. HSLDA agreed to help the family get to Canada and file a claim for refugee status. Our thought was that this test case, if successful, could pave the way for an American asylum claim as well as start the process for creating public awareness in Germany. However, in God’s providence, other events were to redirect that path.

“We Didn’t Want to Leave”

Also back in 2006, a friend asked Uwe and Hannelore Romeike how their children were doing at the local German public school. Already the Romeikes were concerned about the school’s environment. They knew from their own experience that public schools were hostile to their faith and to the values they wished to instill in their children. Their two older children complained that the school was too noisy and that some of the other children were rough. As Uwe and Hanne reviewed the materials that the children brought home and learned about their classes, they grew increasingly concerned. Some of the school’s teachings undermined the truths of their faith and seemed to encourage children to rebel against their parents. Hanne shared her concerns with the friend, who then asked if the Romeikes had thought about homeschooling their children.

“I thought it was illegal,” Hanne says. “My friend told me that it was, but that the authorities did not aggressively pursue homeschoolers in the area. The more I thought about it, the more I became convinced that this was the best way for our children to be raised by us as their teachers. So I asked questions to those homeschoolers in the area about it. They told me the same thing—that we might have to pay some fines but that was about it. They were wrong.”

After attending public schools in Germany throughout childhood, Uwe and Hanne met during their first year at university and were married a few years later. The couple settled in Bissingen, where Uwe (a piano teacher) and his father built a custom home, featuring a music studio on the first floor and living space above. The couple enjoyed living near family and friends and became members of a local Evangelical Free church in which Uwe served as an elder.

In September 2006, Uwe and Hanne began homeschooling their school-age children by enrolling them in the Philadelphia School, a German correspondence school not approved by the German government. In the same month, the European Court of Human Rights denied the Konrad petition that banning homeschooling is a violation of parents’ right to educate their own children. The previous year, the education minister of the Romeikes’ state, Annete Shavan (later to become the federal minister of education) had stated that while homeschoolers in Baden Wurttemberg were “not a problem,” homeschooling should not be tolerated and that in the future more aggressive measures should be taken against it. Unaware of either of these two events, the Romeikes expected perhaps minor troubles, which homeschooling friends assured them they could get through if they stayed firm.

“I remember asking other homeschoolers if the police might come,” says Hanne. “They laughed and said, ‘Oh, Hanne, that would never happen.’”“When Principal Rose of the local school came to meet with us because our children hadn’t come to school, he asked us what we would do if the police came,” she recalls. “We thought he was just threatening. The next month we were shocked when the police did show up one morning without any notice and took the children to school. It was quite traumatic for the children. They came again the next day and, if our friends and neighbors hadn’t intervened, the police would have taken the children again and come back. This was a very scary experience for us.”

At this point, Uwe realized that Germany might not be a place where his family could stay.

The Romeikes had to leave their family, friends, church, and home (above) in Bissingen, Germany

“We knew that our faith demanded that we teach our children ourselves,” Uwe says. “But all over Germany we saw cases of homeschoolers being persecuted.”

He ticks off examples: “Fifteen-year-old Melissa Busekros was put in a psychiatric clinic and a foster home. The Gorbers’ children were removed. The Dudeks were sentenced to 90 days in jail.”

“So many families had left Germany,” he remembers. “We didn’t want to leave: our parents were getting older. We had many friends. I had many students. But we felt that our home could no longer be our home. In order for our family to be safe, we would have to go.”

A Dramatic Move

HSLDA first learned of and reported on the Romeikes’ case in late 2006. The following year, I (Mike Donnelly) travelled to Germany for a homeschool conference. In my presentation at the conference, I spoke about pluralism and encouraged the families to stay strong in their fight for freedom. I also shared the history of homeschooling in the United States, where the early years hadn’t been so different from what German homeschoolers were currently dealing with.

One of the families I met on that trip kept me informed about the Romeikes’ situation, and asked me to get in touch with Uwe and Hanne to advise and encourage them. When I called Uwe, I learned that he was being fined thousands of dollars and that the authorities were preparing to bring an action to put a lien on his home for the payment of the fines. I knew that this was only a starting point and that it was very likely that more severe action would eventually be taken. He told me that he and Hanne thought that they might have to leave Germany.

“Mike Donnelly told me that if we decided to leave Germany and come to the United States, HSLDA would support us in a claim for political asylum,” remembers Uwe. “He said it would be a novel case and that there was no telling how it might turn out. Hanne and I thought it over. We could go to other places in Europe, but America, as we found out, had the freest laws for homeschoolers.”

We knew that we were really in God’s hands but the uncertainty was hard for me. I don’t like surprises.

To help the Romeikes think through the option of coming to the United States, I asked them to get in touch with Reinhard Klett. When I met Reinhard, he was a German citizen working for a large German corporation in Tennessee. He and his wife, Emily, were homeschooling their two boys. Out of a desire for other German families to experience the same homeschool freedom that he was enjoying in the United States, Reinhard called me at HSLDA one day offering to translate documents, make contacts, and help in any other way. His counsel became invaluable to me in helping me understand the issues involved and the cultural differences between America and Germany.

His compassion and sympathy for German homeschoolers was partly a result of an experience his own uncle had with the Third Reich. Reinhard describes the situation. “In 1936 my uncle refused to enroll his children in the Hitler Youth. He received a letter from the local Hitler Youth leader. I had a copy of this letter and when I read the letters that the Romeikes had received I was struck by the similarity in tone and language. I was outraged that 70 years later this mindset might still exist in my homeland. I was determined to do whatever I could to help both this family and German homeschoolers.”

“When Mike Donnelly asked me to discuss with Uwe what would be involved in moving to America, I was struck by the fact that Uwe was from the same part of Germany where I had grown up,” Reinhard continues. “I was convinced of God’s hand clearly at work.”

Uwe, Hanne, and their five children board a plane bound for the United States in August 2008

After a weeklong visit to Morristown, Tennessee, Uwe was convinced that God was leading his family to take a step of faith.

Selling one of his pianos to fund the flight to freedom, Uwe Romeike and his family arrived in Atlanta in August 2008, with little fanfare and only their suitcases. They were met by the Kletts, who provided them with housing in a duplex rental unit. Local homeschoolers gave them a warm welcome.

Tense Moments

Because the asylum application process tracks differently than the regular immigration process, the Romeikes’ application was sent directly to an immigration judge for a hearing, instead of to an immigration officer for an interview. During the nearly two years it took for the asylum application to make its way to a judge, the Romeikes continued to homeschool and build a life for themselves in Tennessee. But as the January 20, 2010, hearing finally drew near, Uwe and Hanne began to feel nervous.

“It’s like when the time for a test comes—the closer it gets the more nervous you get,” says Uwe. “We knew that we were totally in God’s hands but the uncertainty was hard for me. I don’t like surprises.”

“It was also difficult to hear the government’s attorney go against us,” he continues. “As he was making his closing argument, I kept feeling lower and lower because he was explaining all the reasons why the judge shouldn’t grant us asylum. Mike and Will told us that we had a good case but they also told us that there was no way of knowing what the judge would decide.”

The Romeikes enjoying the freedom to homeschool without fear at their new home in Tennessee

Like many administrative hearings, this one was less formal than a hearing for a civil or criminal trial. Judge Burman was businesslike in his handling of the hearing. He showed interest in the issues at stake, but was clear in his articulation of what he needed to know in order to make a decision. He wanted HSLDA to clearly explain how restricting the Romeikes’ right to homeschool constituted persecution. I was able to testify for about 45 minutes, explaining the increasing mistreatment of homeschoolers in Germany as the movement has grown over recent years. Then Uwe and Hanne took the stand to describe how their family had been personally impacted by this treatment.

It was clear that the judge had reviewed much of the brief that we submitted. Although the government attorney, John Cook, had not submitted a reply brief, Cook was well versed in the issues.

In most cases, the judge makes a decision on the day of the hearing, but the government had not completed its routine background checks of Uwe and Hanne. After several recesses in which the judge expressed hope that the background checks would come back, he adjourned the hearing until January 26. (Background checks are run routinely for any asylum application to make sure that the applicant has not committed any crimes since arriving in the country. In many cases, criminal applicants are rejected.)

We all left Memphis disappointed in not having received a decision. However we knew the matter was in God’s hands and we continued to pray.

An Extraordinary Victory

The following Tuesday, all the parties gathered in a conference call connecting Memphis, Purcellville, Houston, and Morristown to hear the judge dictate his decision. In a 28-page, 35-minute decision, the judge granted the Romeikes asylum because homeschoolers were a persecuted particular social group in Germany, because the Romeikes’ religious motivation impressed the judge, and because Germany’s policy of persecuting homeschoolers would circumscribe the exercise of their faith.

The decision was an extraordinary recognition of the fundamental importance of the right of parents to raise their children according to the dictates of individual conscience. Judge Burman noted that the rights being denied the Romeikes were “basic human rights that no country has a right to violate.”

Ironically, the Romeikes were unable to hear the judge’s voice on their phone line. After the call, they had to call me directly to find out what he had decided.

The Romeike family in 2008

“We were so relieved!” Hanne recalls. “We had been trying hard not to get our hopes up too high. Mike and Will had assured us that even if we lost at this level, we would appeal and that an appeal could take years. So we knew that we wouldn’t have to go right back to Germany. But to win at this point was such an answer to prayer. Our children were jumping up and down and everyone in the room was hugging us and celebrating. Tears were flowing in gratitude for God’s protection for our family.”

At HSLDA, we were also celebrating. We had hoped for a positive opinion, but nothing prepared us for the thoroughness of the judge’s decision in our favor.

The decision’s impact in Germany was felt almost immediately as the Associated Press broke the news. The story has since been picked up and carried not only in major U.S. and German papers, but also across every continent. Early on the morning following the decision, both the Romeikes and I began receiving calls from Stern TV, one of Germany’s largest private television networks, seeking an exclusive interview the following week.

German homeschoolers were delighted. They couldn’t believe an American judge would give them this kind of positive recognition—to many it was nothing short of miraculous. Although they have long been very grateful for the steady support American homeschoolers have given, it seemed like a dream come true that an arm of the United States government—Judge Burman—had actually granted asylum based on the right to homeschool. To be able to say that homeschooling is a human right, and that one of the world’s largest countries was willing to grant asylum to preserve this right, has given German homeschoolers fresh resolve and encouragement.

A Freedom to Defend

As Americans, we enjoy great freedoms guaranteed by our constitutions and laws. Among these freedoms is the right to direct the education and upbringing of our children—a fundamental right recognized by the United States Supreme Court in the landmark case Pierce v. Society of Sisters and its progeny. This right has not only been recognized by the Supreme Court, but has also been noted in the constitutions of other countries and in international treaties and declarations.

Interacting with the Romeikes, the Dudeks, the Gorbers, and many others who have been persecuted over something as basic and fundamental as their choice to homeschool helps me to remember how unique the American republic is. Although we face challenges, our country remains a beacon of hope and opportunity to billions all over the world.

Photo credit: Cover image by Ian Reid. All other photos courtesy of the family.